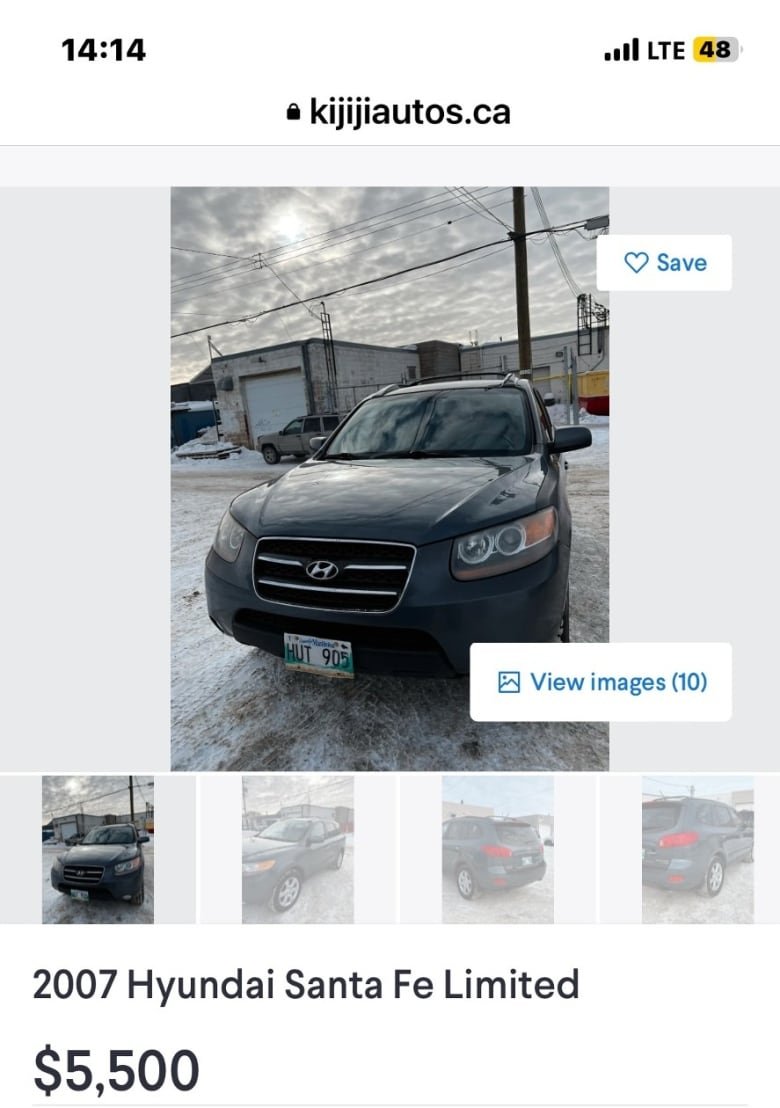

Last winter, Tara Harper had good reason to think she was buying a safe vehicle. The used SUV had recently passed a safety inspection at a Winnipeg Canadian Tire.

But when it broke down just 20 minutes after she handed over $5,000 to the private seller in early February — the 20-year-old college student found herself with a vehicle too dangerous to drive and no recourse.

“My car just suddenly broke down in the middle of a turning lane,” said Harper, who worked minimum wage jobs for more than a year to afford the 2007 Hyundai Santa Fe. “I was really, really furious. It was my first car.”

The seller fixed the engine problem, but it made Harper question how safe the vehicle really was despite what Canadian Tire said.

So in early March, she brought the vehicle to Todd Holmes, a certified mechanic and a family friend.

-

Got a story? Contact Rosa and the team at GoPublic@cbc.ca

“As soon as he put it on the hoist, he told us he was going to stop right there because it was an instant fail. We shouldn’t drive it,” said Harper’s dad, Paul Skirzyk.

The frame was corroded, Holmes said. His finding was later confirmed by Manitoba Public Insurance (MPI) during a third inspection on March 30 — which also found 10 more safety issues.

“It could be very catastrophic,” Holmes told Go Public. “You have a frame that disintegrates during an accident, it could cost someone their lives.”

Automobile consumer protection expert George Iny says provincially mandated vehicle safety inspection systems can leave consumers with a false sense of security, and drivers are being “lulled” into thinking that those inspections guarantee the vehicles being purchased are safe.

“If you knew you’re buying at your own risk, then you wouldn’t have the illusion that the government is covering your back … buying the illusion of protection can be worse than no protection,” said Iny, who heads the Automobile Protection Association (APA), a non-profit that advocates for vehicle safety.

According to Iny, some provincial safety standards inspection systems lack oversight and don’t include key parts of the vehicle. Most complaints to the APA come from Ontario, he says.

Canadian Tire reimbursed cost of vehicle

Harper and her family fought for compensation for more than three months. They say the seller blamed Canadian Tire for failing to catch the problems, MPI wouldn’t help and a manager at the Canadian Tire location said it wasn’t the company’s problem.

“He said once it leaves his shop, he’s no longer responsible. So what is the point of the safety [inspection] if the moment it comes out of your garage, the safety is null and void?” asked Skirzyk.

Canadian Tire told a Winnipeg student the used SUV she was about to buy was safe to drive — but she quickly learned it had major problems.

Go Public contacted Winnipeg’s Polo Park Canadian Tire franchise and the company’s head office. They then reimbursed Harper what she paid for the vehicle, calling it a “goodwill gesture,” according to an email from the company’s head office.

The company told Go Public that all “protocols were followed” by the location that did the initial inspection and that the authorized mechanic “believed that the vehicle met the requirements” to be granted a Certificate of Inspection, indicating it was safe to drive.

Canadian Tire said the damage to the frame could have happened when the engine was replaced.

“We do not know if other modifications were made to the vehicle by the previous owner and as such, cannot comment on the vehicle’s condition after the … inspection was completed at Canadian Tire,” a company spokesperson wrote in an email to Go Public.

Holmes says that’s not possible, since the damage was caused by corrosion, which would take more than the two months that passed between inspections.

After Go Public questioned MPI about Harper’s situation, the public insurer suspended Canadian Tire’s Polo Park location from doing inspections for the provincial program for 12 months on Aug. 10.

In an email to CBC News, MPI said the location’s permit was suspended “for failing to act with honesty and integrity, and for issuing inaccurate or incomplete inspections.”

Manitoba issued 54 suspensions in 5 years

Go Public asked the provinces how many times they’ve sanctioned garages for botching inspections over the past five years.

Most didn’t respond or said they don’t track that information. Manitoba posts the information online, indicating it has issued 54 suspensions to safety inspection stations and individual mechanics over that period of time.

The Ontario Ministry of Transportation would not provide the numbers on request.

P.E.I., which is the only province that requires vehicle safety inspections every year even with no change in ownership, says it has issued 22 warnings to garages and 21 warnings to individual mechanics.

The province says 16 garages and 41 mechanics were suspended from doing inspections.

Quebec’s Société de l’assurance automobile du Québec (SAAQ) says it has banned 11 garages and temporarily suspended 10 from doing the safety inspections over the past five years.

Engine, transmission not ‘safety components’: province

Iny says the vehicle’s frame — the main issue with Harper’s SUV — should have been covered in any safety inspection, but other important parts of the vehicle are not.

He said engines are generally not inspected unless a warning light is on — but they’re easy to turn off if you have a shady seller.

Another example: he says that often the transmission is not inspected unless there are obvious leaks.

“You’re just protecting businesses when you have a bad inspection system,” he said. “You’re not actually protecting the customer.”

Iny says car buyers shouldn’t rely on provincially required safety inspections. Instead, they should have vehicles assessed by an independent mechanic to ensure they’re safe.

“Spend a little extra money and have a vehicle checked before you buy it,” he said.

MPI says the province’s inspection program “focuses on ensuring that vehicles meet minimum safety standards” like functioning brakes, good tires, headlights and taillights.

It says engines and transmissions aren’t included in inspections because they aren’t “considered safety components of a vehicle,” which is the case in many provinces.

It says safety components are outlined in provincial regulation. Like Iny, MPI suggests that in addition to the provincial safety inspections, buyers should have vehicles inspected by a trusted mechanic before purchase.

Private sales bring added risk: expert

Harper also wonders what the seller knew about the car. Go Public reached out to him repeatedly, but didn’t hear back.

While used car buyers may get a better price through a private sale, according to Iny, it is more risky than going through a dealership.

Dealers are bound to follow safety inspection and consumer protection laws, as well as disclosure rules on vehicle pricing and accident, repair and registration history.

Unlike private sales, if a customer feels cheated, they can ask for help — and sometimes get compensation — from the provincial dealer authority.

Harper and her dad tried to buy from a dealership, but in a tight used car market they couldn’t find what they needed and turned to Kijiji.

Her family says that given the cost of repairing just the frame is about $4,000, they plan to tow the vehicle to a junkyard soon.

They say the experience has changed Harper’s views on owning a vehicle and left them with no trust in provincial safety inspections.

Submit your story ideas

Go Public is an investigative news segment on CBC-TV, radio and the web.

We tell your stories, shed light on wrongdoing and hold the powers that be accountable.

If you have a story in the public interest, or if you’re an insider with information, contact gopublic@cbc.ca with your name, contact information and a brief summary. All emails are confidential until you decide to Go Public.