When “Bobby Brown” sent me a direct message on Instagram, I knew right away he wasn’t the real deal. A tall, handsome, 40-something man who said he’d found my social media profile and become enamoured.

“Nice smile,” he wrote. “I’m Bobby Brown from Sacramento, California, USA. Currently living in Scotland working here as an oil drilling engineer.”

Usually, I delete messages from strangers who reach out on social media claiming to be soldiers, surgeons or, like “Bobby,” oil rig engineers. An uncannily high number claim they are widowed.

I suspected this online Romeo was running one of the most popular cons going — the romance scam.

With Valentine’s Day approaching, Go Public asked the Canadian Anti-Fraud Centre (CAFC) for statistics on romance scams and received some staggering figures.

Romance scams were responsible for some of the highest financial fraud losses in 2023, according to the CAFC, costing 945 victims more than $50 million. That means each person lost an average of almost $53,000. And that only reflects the fraud that victims reported to authorities.

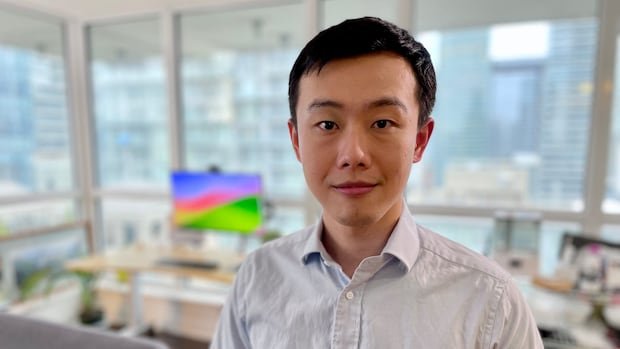

Rather than scoff at people who fall prey to romance scams, social psychologist Andre Wang says people should understand what drives that need for connection.

“It’s actually tapping into something that’s quite fundamental about who we are as human beings,” says Wang, assistant professor of psychology at the University of Toronto. “This fundamental need to belong.”

After six weeks of messaging back and forth with Bobby, I finally called him out and asked him to come clean about his life as a romance scammer, how he does it and why he says he can’t stop.

How he wooed me

After Bobby introduced himself as an oil drilling engineer, he explained he was working in Scotland on a short-term contract and had a nine-year-old son in a military boarding school in the U.S.

“Can I have your mobile number?” he asked right away, claiming that his laptop battery was almost dead so he’d need to switch to texting on his phone.

Over the next couple of weeks, Bobby asked for my number repeatedly. I learned later that he was worried that if one of the many other women he was corresponding with reported the phoney account, Instagram would shut it down.

Within two weeks, he was calling me “dear” and “sweetheart.”

He came on pretty heavy — and his English didn’t always make sense. “Well you are really an interesting woman, I would love to be a part of you,” he wrote.

“I want you to be MINE and I want to love you til the end of the world,” he messaged.

In the meantime, Bobby sent a photo of what he claimed was a street in Edinburgh where he was working — only the cars were parked on the wrong side of the road, as people in Scotland drive on the left.

We made small talk and I asked him about his favourite meal, which he claimed was “macaroni and spaghetti with garlic” and sent a photo of a pasta dish. (Later, he told me he googled “popular American foods” to find an answer — he must have misunderstood the results.)

To prove he was legit, he sent a photo of a staff ID card, bearing the name Bobby Brown and said he was an oil spillage controller for an oil and gas company based in Aberdeen, Scotland. Oddly, the signature below the photo looked nothing like “Bobby Brown.”

At the six week mark, the dashing oil engineer proposed.

“Will you be mine?” he asked, adding an emoji of a diamond ring. “I want you to own my heart. I think this love will last forever sweetheart.” Yes, he included a red heart emoji.

Finally, I’ve reached my limit. Though I’ve been waiting to see how he planned to convince me to send him money, now, I’m ready to hear the truth.

“I would just like to have an honest conversation,” I write. “Will you do that?”

Silence. Then, blue dots appear on my phone as he types. They disappear. Reappear. Finally, he responds.

“You are going to hate me.”

To my surprise, he agrees to talk, as long as CBC keeps his identity concealed, because he says speaking out about the shady world of romance scams will put his safety at risk.

An online romance scammer tried to catfish CBC Go Public reporter Erica Johnson, who called him out and convinced him to do an interview.

‘Yahoo boys’

The phone line is crackly, his voice barely audible. I’ve dialed a number with the area code for Rochester, New York, but the scammer says he’s rigged the phone so he can talk to women from where he actually lives — Oghara, in southern Nigeria, with a population of about 290,000.

It’s evening there, and he says he’s walked to a deserted field, where no one can hear his conversation.

He says he’s 27, the oldest of several siblings. He tells me that six years ago, his father lost a good job and has struggled to find work. His mother was pregnant and out of work at the time, he says.

“We had to sell our house to survive,” he tells me. His voice cracks. If he’s lying, he’s doing a convincing job.

Poverty is widespread, he says, and getting worse. According to a report by the Nigerian government, inflation hasn’t climbed so high since the mid-90s.

He tried to get odd jobs for a little cash, he says, but most days came home empty handed.

Reluctantly, he says, he decided to become a “Yahoo boy” — a nickname that comes from the email service Yahoo, which became a popular tool for online fraudsters in Nigeria.

He estimates 80 per cent of the people he knows are Yahoo boys, most of them committing romance scams.

Though he says it’s not something people in Nigeria look upon favourably, “they can’t force it to go away” because “families need it to survive.”

‘The boss’

After his dad lost his job, he says he moved into an apartment where an older man — “the boss” — provided a bed and one meal a day.

In exchange, he says he and two other Yahoo boys who lived there were required to catfish — pretend to be other people online, seduce foreign women, win their trust and eventually convince them to send money.

The boss would take half their earnings, he says.

Late in the evening — when women in North America were just waking up — he says his boss would call his three recruits to the living room.

“Get your social media accounts ready,” he says the boss would tell them. “Start hustling.”

The boss provided photos of attractive Caucasian men to use as their catfishing profile pictures — stolen from social media accounts, he says.

He also gave them scripts for various scenarios, explaining what to say as an oil engineer, a doctor or someone in the military, as well as how to use flattery, and excuses for when the targeted women would ask to meet in person or talk on the phone.

The scammer says he was told to claim he had a son, because women generally like young children. “It helps build trust,” he says. A child also figures prominently in his scams.

‘The Method’

During his time with the boss, the scammer says he learned how to pull off what was called “The Method” — a scam that involves asking women for photos of Apple or iTunes gift cards. He then trades the codes on those cards on the black market for cash.

He says he’d sometimes tell his marks that he needed gift cards to buy data for his phone. He’d claim he was having trouble accessing his bank account from another country but desperately wanted to stay in touch.

The young son he mentions when he first connects with them comes in handy, too.

“I’m just going to tell [her] that my son needs the gift card for his subscription on his mobile phone. And games,” he says. “Keep sending them every three days.”

He says he tells her that he’s going to pay her back and that when he’s done his overseas contract, she’ll benefit from a loving relationship with a handsome and financially secure man.

“The woman won’t want to miss out,” he says.

While people might question why women might provide emotional or financial support, Wang, the psychologist, says it’s normal human behaviour for someone who believes they’re in a relationship.

Social psychologist Andre Wang explains how ‘motivated reasoning ’ can affect our behaviour in romantic relationships — and shares a tip for how to avoid online romance scammers.

“We’re supposed to support people with whom we have romantic bonds,” says Wang.

“Romance scammers can definitely tap into that sense of obligation that people feel when they are intimately connected with another person,” he says. “Even a simple request that might seem outlandish from an observer’s point of view might feel different when you are the one being asked.”

The scammer says they were coached to never ask women to wire money, because “they might be told the whole truth at the bank” and months of effort could be lost.

When “The Method” didn’t work on a woman, he says the boss beat him. He claims that when he didn’t earn enough, the boss would sometimes purposely serve him food that would make him sick.

After two years, he says he fled and moved back home, where he now mostly runs online romance scams on his own.

He’s tight-lipped about how many women he’s tricked and how much money he’s bilked out of them over the past six years, saying only that most victims have been in Canada or the United States.

Some of the bigger windfalls — $2,000 or $3,000 US — are the result of a fraud that pulls on the heartstrings of the women who fall for it: “Billing.”

Billing

In this scam, he sends a frantic text to the woman he’s courting, telling her his young son living in the U.S. has been rushed to an emergency room. He urgently needs to send the hospital a $3,000 deposit, he says, but can’t access his bank account from Scotland.

He tells me that because it’s such a big ask, he texts the woman a photo of his son in a hospital bed, with doctors at his bedside.

In reality, he says it’s all been Photoshopped.

“You get the proof to make the client trust,” he says. “Whatever I ask of her, she gives to me.”

He says he knows that preying on the generosity of women he’s misled for months is wrong, but poverty and desperation to feed his family trump feeling bad about the manipulation.

Though a request for such a large amount of money may seem like an obvious scam, Wang says some women follow through because of a psychological process called “motivated reasoning.”

“We tend to put more weight into evidence that supports our sense of reality, and we’re more likely to disregard evidence pointing to the contrary,” he says. “We are confirming what we want to believe.”

The scammer says he studied my Instagram account, and would definitely have asked me for gift cards for his non-existent son. He says he might have tried “The Billing” scam, too.

Our phone call has stretched past midnight in Nigeria, where it’s started to rain. He’s shivering and says he has to end the interview.

He’s hoping I’ll mention how sorry he is for ripping women off, for breaking their trust and their hearts. He says he understands why they might be angry with him.

“I know the kind of life I’m living,” he says. “I don’t have money.”

“I feel badly, but I’ve got no option.”

If you think you or somebody you know may be a victim of a romance scam, report it to the Canadian Anti-Fraud Centre.

Later this week, CBC News: Marketplace goes overseas to uncover a long-term con that combines investment schemes, romance scams and cryptocurrency fraud. They also speak to perpetrators who reveal how they’re forced to scam Canadians. “Bad Romance: Who’s conning Canadians” airs Friday, Feb. 9 on CBC News: Marketplace.

Submit your story ideas

Go Public is an investigative news segment on CBC-TV, radio and the web.

We tell your stories, shed light on wrongdoing and hold the powers that be accountable.

If you have a story in the public interest, or if you’re an insider with information, contact gopublic@cbc.ca with your name, contact information and a brief summary. All emails are confidential until you decide to Go Public.